Recommended Ressource:

- [Video EN] Understanding MBA

- [Post FR] Obfuscation with Mixed Boolean-Arithmetic Expressions : reconstruction, analysis and simplification tools

- [Tool] MBA Online Tester

Mixed Boolean Arithmetic

Original lesson from https://plzin.github.io/posts/mba

What does the following function do?

int hmm(int x, int y) {

return (x ^ y) + 2 * (x & y);

}

The function computes the sum of x and y using Mixed Boolean-Arithmetic (MBA). Here’s how it works:

- $x \oplus y$ computes the sum without carries.

- $x \land y$ identifies where carries occur. Multiplying by 2 shifts these bits left, placing them correctly for addition.

In essence, the function adds x and y using bitwise operations.

Automating MBA Expressions

We can automate the generation of MBA expressions. Here’s an example function:

int what(int x, int y, int z, int w) {

return 4071272 * w + 3590309086 * (w | z & z & (y |

w)) + 3690425492 * (w & x ^ ~z ^ ~y) + 3735539420 *

(y ^ (w & z | y)) + 3176111544 * ((x & y | x ^ z) ^

~y) + 90227856 * (y & x & x & (x & w | ~w)) +

2231609705 * (~z ^ w & x | z ^ x | x | w) +

263864489 * (w ^ z | x | w | z) + 17029904 *

(~w ^ w ^ (x | z) ^ ~x) + 2987805917 * (z & x) +

1280785607 * z + 2092481170 * (y & (w & y | ~z)) +

637019375 * (~w | w & z & ~x) + 3221225472 * ((x |

w) ^ x ^ x ^ y) + 3985988880 * x + 263864489 * (~~w &

x) + 469200020 * ((z ^ w & w) & ~(x ^ y)) +

1774328762 * ((w | x) & (x ^ z) & z) + 3645311564 *

(~(z | w) | w) + 3194849700 * ~((y | y) ^ y ^ z)

+ 1678283628 * ~(~y & ~w) + 1083630375 * y;

}

It again computes $x + y$. The values of $z$ and $w$ do not matter.

Basics

There are two primitives used in MBA expressions:

- Linear MBA identities: Linear combinations of boolean expressions. Example: $x + y = (x \oplus y) + 2 \cdot (x \land y)$.

- Permutation polynomials: Permute $w$-bit integers. Example for 8-bit integers: $p(x) = 196x^3 + 48x^2 + 75x + 116$ and $q(x) = 16x^5 + 124x^3 + 96x^2 + 35x + 36$.

Permutation polynomials can be turned into MBA expressions by choosing coefficients with small Hamming weight or rewriting multiplications by constants with linear MBA.

The challenge is to generate these expressions automatically.

Linear MBA

To me personally, this seems like it should be the more difficult problem of the two. It seems like there should just be some neat formula to find the inverse of a permutation polynomial, but historically this problem was solved first.

Automating Linear MBA Identities

How would you go about automatically creating linear MBA identities? In the first code example, there was this neat explanation that $x \land y$ are the carry bits which are shifted by multiplying it by 2 and $x \oplus y$ is addition without carry. Obviously, such explanations won’t always exist or be automatically derivable.

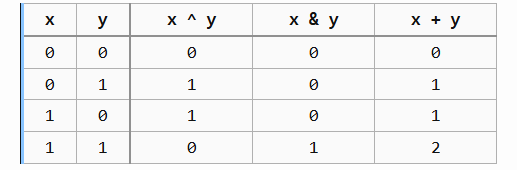

Let’s still use that as an example: We want to rewrite $x + y$ using $x \oplus y$ and $x \land y$. What you can do (for any function whatsoever), is make a table of the outputs for both the rewritten expression ($x + y$) as well as the expressions used for rewriting ($x \land y$, $x \oplus y$) for all possible inputs. We will assume $x$ and $y$ are 2-bit numbers.

By adding the corresponding columns (and multiplying the $x \land y$ column by 2), you can verify that indeed $(x \oplus y) + 2 \cdot (x \land y)$ equals $x + y \pmod{4}$.

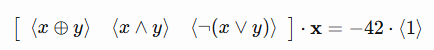

We can write this in matrix form as:

The columns of the matrix $A$ are the $x \oplus y$ and $x \land y$ columns from the table. The entries of the vector $x$ are the coefficients of the linear combination. The vector $b$ is the $x + y$ column from the table. Maybe you can see where this is going. We construct the matrix $A$ and the vector $b$ and solve the linear system of equations $Ax=b$.

There are just two problems with this:

- The full table would be 16 rows, or $2^{wn}$ where $w$ is the integer width and $n$ is the number of variables. This will be way too big for realistic $w$. We are looking for integer solutions and the equations are modulo $2^w$. You could say we are solving the system over $\mathbb{Z}_{2^w}$ which are the integers mod $2^w$. Unfortunately this is not a field, meaning usual linear algebra won’t work, i.e. standard gaussian elimination can’t solve this.

- The second problem will be the topic of the second post in this series. The first one we can address right here. There is one crucial property we haven’t used yet. In the above construction we can use any function for rewriting, it doesn’t have to be a boolean expression, which is nice, but only in restricting the class of functions does this actually become practical. Because unlike general functions, boolean expressions are just applied bitwise, meaning the value of bit $i$ of the output only depends on bits $i$ of the inputs. I will refer to functions with this property as bitwise functions. Basically any function $f:{0,1}^n \to {0,1}$ that is applied to each bit separately is a bitwise function. (There are 16 such functions with 2 inputs or $2^{2^n}$ in general). For example bit $i$ of $x \cdot y$ depends on a lot of bits and not just bit $i$ of $x$ and bit $i$ of $y$, so it is not a bitwise function whereas $x \land y$ is.

It is this property of bitwise functions that makes it possible to restrict the inputs we have to consider to just 0 and 1 for each input. This is what I call the “Fundamental Theorem of Mixed Boolean-Arithmetic”. It will be proved in Part 1.5. In the example above, we would only have the following table with 4 rows instead of 16 or in general $2^n$ instead of $2^{wn}$.

$x + y$ is not bitwise, why is it still allowed? That’s because the set of functions allowed is actually slightly bigger. Linear combinations of bitwise functions are also allowed. Supplying a linear combination of bitwise function instead of supplying the bitwise functions separately amounts to limiting the coefficients that are allowed in the linear combination. $x + y$ is just a linear combination (with coefficients 1) of the identity functions on $x$ and $y$.

Permutation Polynomials

There is a simple characterization of permutation polynomials which allows us to generate them very easily. This characterization is due to Rivest:

A polynomial $p(x)=a_0 + \cdots + a_d x^d$ over $\mathbb{Z}_n$ is a permutation polynomial if and only if

$a_1$ is odd $a_2 + a_4 + a_6 + \cdots$ is even $a_3 + a_5 + a_7 + \cdots$ is even The problem then, is finding the inverse to such a polynomial. As mentioned, this is not trivial in general, but we can quickly take a look at a simple example where $d = \deg(p) = 1$: $p(x) = a_1 x + a_0$. These are used as Linear Congruential Generators (although the modulus need not be a power of two) that are used as very simple (and definitely not cryptographically secure) random number generators.

The following discussion is not strictly necessary to understand the rest of this post. It is more for the fun of it.

It is fairly easy to see that the value of $a_0$ neither makes nor breaks a permutation polynomial and can be chosen freely. Let’s set $a_0 = 0$. What values can $a_1$ take? It is pretty clear that $a_1$ can’t be even, otherwise $a_1 x$ can only be equal to an even number mod $2^n$. But it can actually equal any odd number. The reason is that any odd number has a multiplicative inverse in $\mathbb{Z}_{2^n}$, since $2^n$ has only the prime factor 2 and thus the greatest common divisor of an odd number and $2^n$ is 1. The inverse $a_1^{-1}$ can be computed with the extended Euclidean algorithm. $a_1 x$ maps to $y$ for $x = a_1^{-1} y$.

We can also easily compute the inverse $q(x) = b_1 x + b_0$.

$q(p(x)) = b_1 (a_1 x + a_0) + b_0 = b_1 a_1 x + b_1 a_0 + b_0 = x$

By equating coefficients, we get:

$b_1 a_1 = 1 \Rightarrow b_1 = a_1^{-1}$

$b_1 a_0 + b_0 = a_1^{-1} a_0 + b_0 = 0 \Rightarrow b_0 = -a_1^{-1} a_0$

So in general the inverse is given by $q(x) = a_1^{-1} x - a_1^{-1} a_0$

For higher degree polynomials this becomes much more difficult and (as far as I know) no easy formula for the inverse of a permutation polynomial exists. But there are algorithms for this, which we will explore in Part 3, in addition to many other details concerning polynomials mod $n$.

Obfuscating Constants

Of course, there are many ways to combine these primitives. One application I particularly like is obfuscating constants. Let’s fix the number of variables $n=2$ and integer width $w=8$ for simplicity. I will be using the following shorthand for bitwise functions $f:\mathbb{Z}{256}^2 \rightarrow \mathbb{Z}{256}$:

which is basically a column of the matrix we constructed before.

Let’s also fix the operations used for rewriting as $x \oplus y$, $x \land y$ and $\neg(x \lor y)$ and the constant to obfuscate as 42. These are sufficient to obfuscate any constant (but they will always result in the same linear combination, so you should provide more if possible).

You might just try to construct the linear system like this:

his is sort of correct, but there are some misconceptions at play here. The constant 42 is not a bitwise function, because there is a different function for bits in different positions: For some bits, it is the constant 0 function, and for the others, the constant 1 function. We know, though, that the rewrite/rewritten operation(s) are allowed to be linear combinations of bitwise functions, so maybe this would work:

This is at least clearly defined, but also wrong. Suppose we initialize an 8-bit number with the constant 1 function. What value would be stored in that number? Every bit would be a one, so the number would be 0xff = 255 or -1 if the number was signed (interpreted in two’s complement). And this will be the clue to getting it right. The constant 1 function represents the number -1 and the coefficient we want is thus -42. The correct equation is

Here is an example with a few more rewrite operations.

uint8_t constant(uint8_t x, uint8_t y, uint8_t z) {

return -115 * (x ^ y) - 41 * (x & y) - 189 * ~(x | y)

- 203 * ~x + 74 * ~y + 20 * z - 20 * (y & z)

- 21 * (x | z) + 21 * (~x & z) + 20 * (y | ~z);

}

Since we’re dealing with 3 8-bit inputs, brute-forcing the equivalence is quick and easy. It took my CPU 28ms, which is insanely fast (even when considering that everything fits into register). This is one of these occasions where I realize how fast modern CPUs are. That being said, we can easily generate an expression with more variables, which would quickly make brute-force infeasible. If we were dealing with 32-bits, this would already be prohibitively expensive with just 3 inputs. I also asked Z3 to prove the equivalence, which took about 4 minutes, so I am pretty sure it just brute-forced it indirectly.

Non-Linear MBA

Continuing with the example of obfuscating 42, we can transform the given linear MBA expression to a non-linear one, by just rewriting the constant factors of the linear combination with linear MBA. We will use the same rewrite operations for the constants but exclude the operation whose factor we are obfuscating. For example, we will rewrite the -115 with the same operations except for $x$ ^ $y$. When we expand the resulting product in each term in the linear combination, we get a linear combination of products of bitwise functions. (Each product appears twice, so we can add the corresponding coefficients). The result is this:

uint8_t constant(uint8_t x, uint8_t y, uint8_t z) {

return 141 * (x & y) * (x ^ y) + 120 * (x ^ y) * ~(x | y)

+ 71 * (x ^ y) * ~x + 27 * (x ^ y) * ~y + 65 * z * (x ^ y)

+ 15 * (y & z) * (x ^ y) + 126 * (x | z) * (x ^ y) + 236

* (~x & z) * (x ^ y) + 187 * (y | ~z) * (x ^ y) + 10

* (x & y) * ~(x | y) + 90 * (x & y) * ~x + 142 * (x & y)

* ~y + 163 * z * (x & y) + 41 * (x & y) * (y & z) + 38

* (x & y) * (x | z) + 148 * (x & y) * (~x & z) + 162

* (x & y) * (y | ~z) + 162 * ~x * ~(x | y) + 147 * ~y

* ~(x | y) + 108 * z * ~(x | y) + 104 * (y & z) * ~(x | y)

+ 89 * (x | z) * ~(x | y) + 193 * (~x & z) * ~(x | y) + 97

* (y | ~z) * ~(x | y) + 106 * ~x * ~y + 162 * z * ~x + 14

* (y & z) * ~x + 8 * (x | z) * ~x + 72 * (~x & z) * ~x + 40

* (y | ~z) * ~x + 125 * z * ~y + 255 * (y & z) * ~y + 114

* (x | z) * ~y + 222 * (~x & z) * ~y + 2 * (y | ~z) * ~y

+ 97 * z * (x | z) + 229 * z * (~x & z) + 211 * (y & z)

* (x | z) + 231 * (y & z) * (~x & z) + 98 * (x | z)

* (y | ~z) + 228 * (~x & z) * (y | ~z);

}

Verifying the equivalence took Z3 100 minutes, so we can assume it is again (indirectly) brute-forcing. (It would be weird if it had to brute-force linear but not non-linear). Again, we could brute-force this faster in C, but this would be impractical for more variables or larger integers.

Another way of generating non-linear MBA is to rewrite the constant 1 with linear MBA, and multiply the result with any linear MBA expression. Expanding this out also gives us a linear combination of products of bitwise functions.

Lastly, we can use permutation polynomials. Given a linear MBA expression, we can plug it into a permutation polynomial and expand the definition of the polynomial. We can then afterwards compute the inverse permutation via the inverse polynomial.

C03-04 : Mixed Boolean Arithmetic

I obfuscated some math operations with MBA. Can you deobfuscate them and retreive the original equation to find the flag?

The flag format is LRCTF{PrintableAscii}.

flag md5sum : 266cf8f027d969cea5e88e5b2e658601